I am wildly passionate about nutrition and wellness. Mostly because I’ve struggled with it my entire life. And no one ever really taught me how to read a nutrition label.

No one in all my years of school ever really taught me anything about nutrition. It’s even pretty fairly accepted that most doctors get little training in nutrition. Here in the U.S. we typically treat symptoms rather than educating the public on root causes (like diet and lifestyle).

I could rant about that whole subject in many dedicated blog posts – but today I wanted to do a little nutrition label 101. I’ll be taking you guys through how I read and evaluate nutrition labels – and also give you a little “insiders” knowledge on how the claims made on the front of the box may be deceiving you.

My disclaimer: I am not a licensed medical professional. Please consult your doctor before making any changes to your lifestyle or diet.

How to read a nutrition label 101

Old labels vs new labels

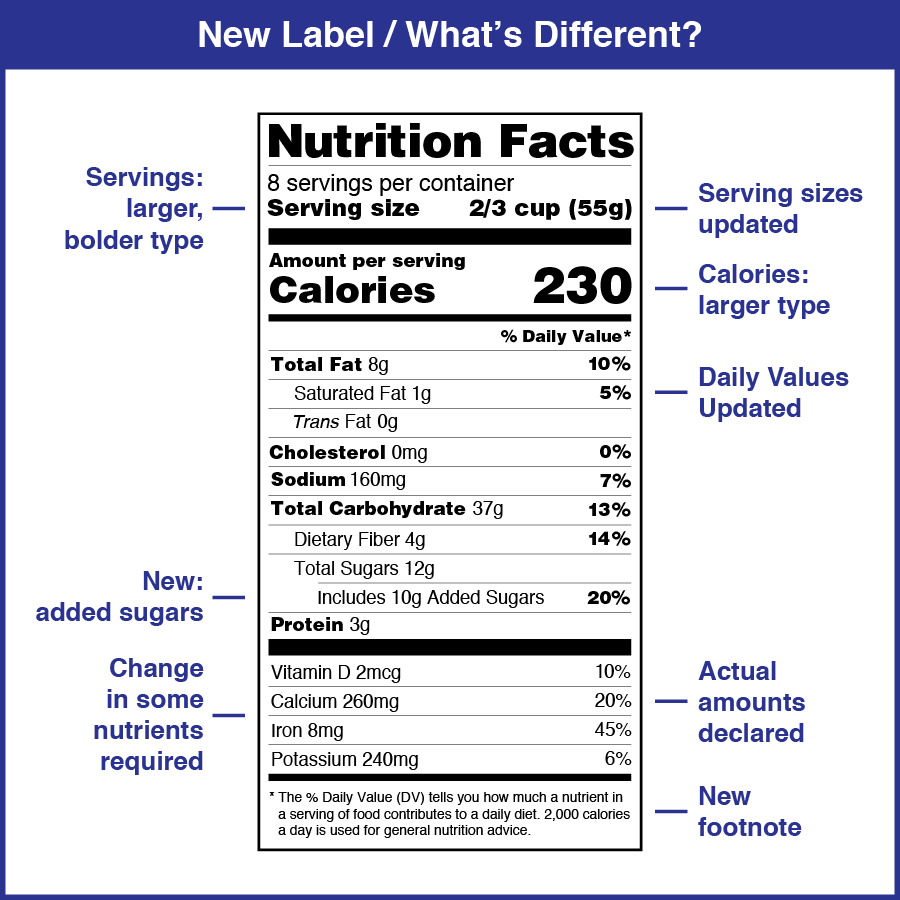

Nutrition labels on some of your favorite foods may be looking a little different lately! That’s because in 2016, the FDA updated its labeling rules for packaged foods to reflect new scientific information. The new labeling system, in theory, should make it easier for consumers to make informed choices.

If you know how to read them properly. Wink, wink.

You can find a side by side comparison of the old label vs the new label here. Manufacturers with less than $10 million in annual sales have until January, 2021 to comply with the new labeling, so we should be seeing this new system in widespread fashion soon.

I found this handy little image on the FDA’s website.

The most important changes to the label you’ll see are that the print size and boldness for calories has been enlarged and made more prominent, serving sizes have been updated to better reflect not the recommended amount but an amount closer to what the average consumer actually eats, and we can now see the split between total sugars and added sugars.

For the purposes of this post, I’ll be referring to the new labeling.

Calories & serving sizes

I personally love the update to the new label which includes making calories much larger and bolder. The real winner of a change, though, is the update to serving sizes. Serving sizes in the old labeling system were smaller – and while the intent of this change wasn’t to encourage Americans to eat more, it was actually to hopefully make people better aware of just how much they’re consuming.

Like, let’s be real. Do you ever really sit down and only eat “one serving” of chips? No, my friends. We eat multiple. Sometimes the entire damn bag.

How to gut check nutritient density on a nutrition label

Alright, you’re walking down the grocery aisle (or shopping online like me, LOL). You see an item you think you like. You grab it, flip it over, and scan the fine print on the nutrition label.

But like – how do you know if it’s “good” for you?

We’re all bio-individuals and one person’s food may be another person’s poison. But there are definitely some ways to “gut check” the nutritional density of the item at hand by scanning the nutrition label.

The facts about fats

There is a lot of conflicting science on the links between fats and chronic metabolic diseases. What is known, though, is that some fats are heart healthier than others. When you can, it’s recommended to opt for items low in saturated fats (and cholesterol), as those fats tend to be the most often linked with things like heart disease.

Unsaturated fats (think like your olive oils, avocados, and salmon) are actually often linked to heart health when eaten in moderation. While I don’t really “follow” Noom anymore, if we were talking in Noom language, the fat category would be red or yellow – meaning enjoy in moderated quantities.

Fiber is your friend

The daily recommendation for fiber is somewhere between 25 to 30g per day – but most Americans eat barely half that amount. Fiber is incredibly important for gut health and creating a sense of fullness.

Keep it regular, people.

Any labels showing 10g of fiber or more per serving would be considered a “good source of” fiber.

Identify added sugars

My favorite part about the new nutrition label is the distinction between total sugars and added sugars.

Some of your favorite (and healthy!) fruits may be high in sugar – but those sugars are natural, not added, and thus processed very differently by the body. Natural sugars are often found in items also high in fiber (like berries), meaning they’re more nutrient dense than items packed with added sugars (and lacking the nutrients).

Added sugars are often snuck into daily items that we don’t even think about – like pasta sauce. My little tip is to just check the label and opt for items with little to no added sugars wherever possible.

“% DV” and what that means

DV’s are the recommended amount to consume each day. The % DV is how much a nutrient in a single serving of a packaged food contributes to your daily diet (source). % DV is incredibly helpful to reference when evaluating the nutrient density of a packaged item as you’re shopping. You’re able to scan the label and gut check if this item contains a significant amount of nutrients – or maybe a significant amount of things you don’t want (like added sugars).

Anything above 7-10% DV can be considered somewhat substantial. But the important thing to know is that there are very specific amounts of nutrients that must be present to use marketing claims on packaging such as “good source of” or “high in” (ex/ “good source of calcium” or “high in calcium”).

Marketing claims you need to know about

Some fast facts about labeling from the FDA website:

- The terms “high,” “rich in,” or “excellent source of” may be used on the label and in the labeling of foods provided that the food contains 20 percent or more of the RDI or the DRV per reference amount customarily consumed.

- The terms “good source,” “contains,” or “provides” may be used on the label and in the labeling of foods provided that the food contains 10 to 19 percent of the RDI or the DRV per reference amount customarily consumed.

There is also no formal definition of, nor real regulation of, the use of the word “natural” on your packaged food products.

I think this clarity in marketing claims standards is important for a couple reasons.

First, just because an item is labeled on the front of the package as “natural” – does not mean the item is good for you or healthy by normal standards. Many juice products can utilize phrases like “natural” or “high in vitamin C,” but these products are also high in added sugars. Cereal is another category that can lean into this subtle marketing deception by labeling items as “a good source of healthy whole grains” – but again, can be packed with added sugars.

Second, as someone with a modest Instagram following, I see a lot of wellness bloggers and content creators verbally claiming some items are “a good source of” something or healthy – and they definitely aren’t making these claims based on the guidelines set forth by the FDA. Likely because few people know about these FDA guidelines. It’s very possible you’ll follow a food blogger who claims an item is “a good source of protein,” but that item being discussed may actually contain very little protein when the % DV is evaluated.

So wtf is my point here?

Packages may mislead you. Influencers and bloggers may mislead you. So you (unfortunately) have to arm yourself with as much knowledge as possible and make the best nutrition decisions you can that are right for you (as decided by you and your doctor).

I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface on this topic – so let’s keep discussing in the comments below.